Filmography

The Worst Movie of 1953

How Hayden Rorke became a late-night-movie mainstayBy Brett White

Hayden's first four years in Hollywood put him onscreen with some of the most famous actors of the era—or any era. By the fall of 1953, Hayden had already been manhandled by Burt Lancaster in Rope of Sand, intimidated young Dean Stockwell in Kim, doled out doctorly advice to Spencer Tracy and Joan Bennett in Father's Little Dividend, buckled swashes against Donald O'Connor in Double Crossbones, waltzed with Nina Foch in An American in Paris, and become a favorite of A-list directors Arthur Lubin and Vincente Minnelli. In 1953 alone he quarreled with Van Johnson in Confidentially Connie and cross-examined his old pal Burt Lancaster in South Sea Woman. But, proof that an actor has no control over their legacy, Hayden would not be remembered for his roles—some of them sizable!—in these films. Instead, thanks to a half century of nonstop, late night reruns, Hayden's filmography would begin and end in the minds of many with Project Moonbase.

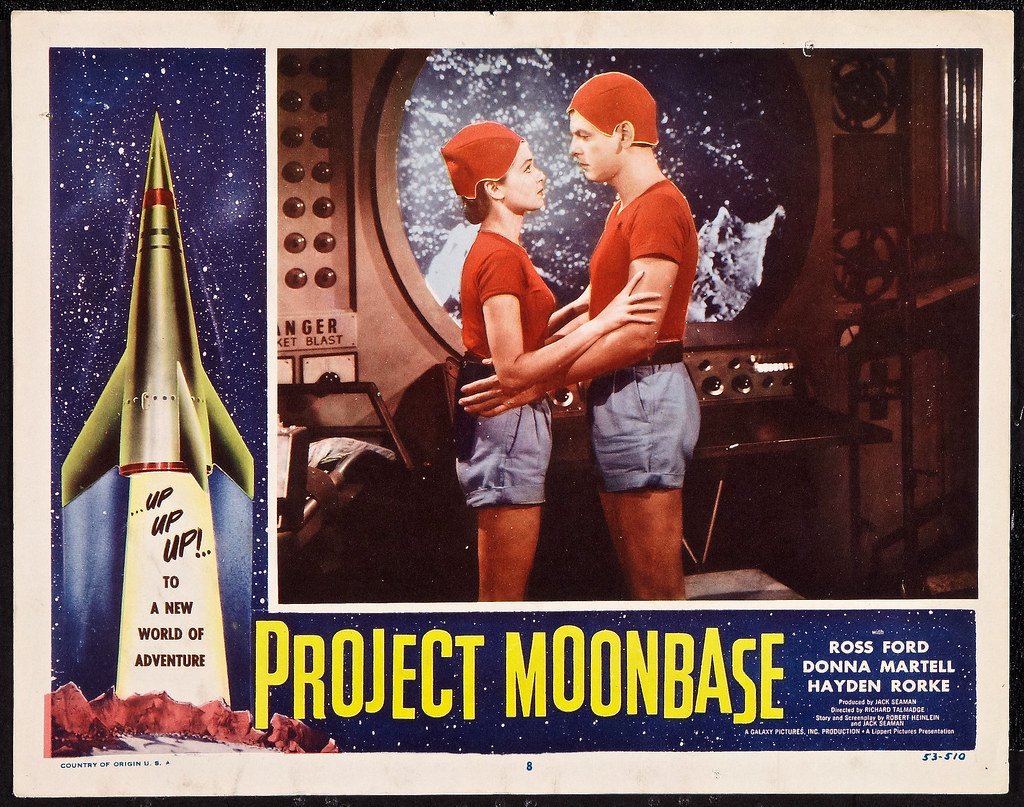

You can sum up Project Moonbase's reputation with five words: Mystery Science Theater did it. Despite a script from sci-fi legend Robert A. Heinlein, the barely-a-film was bad enough, notorious enough, and cheap enough to get a feature-length ribbing by Joel with the help of his robot friends in 1990 during the cult fave's debut season. This should come as no surprise to anyone who's seen even a minute of Project Moonbase, an unintentionally campy sci-fi cheapie where astronauts dress like bartenders at a WeHo gay bar. Your jaw will drop at the sight of dignified Dr. Bellows wearing a swimming cap, tight cap-sleeve t-shirt, high-waisted short shorts, and black combat boots.

And just to top it all off, Hayden plays General "Pappy" Greene.

Set in the distant future of 1970, Project Moonbase follows soldiers in the United States Space Force as they launch a project to build a base on the Moon. Note that this is not a film set on a Moon base, but rather a film about a rocket's journey to the Moon to survey potential locations for a moon base. Standing in the way of Colonel Briteis (Donna Martell) and Major Bill Moore (Ross Ford) is a saboteur posing as the Moonward-bound rocket's doctor (Larry Johns). His plan: seize control of the rocket and ram it into the United States' orbiting Space Station, thus destroying Earth's outer space ambitions. The Enemy of Freedom, as the opening crawl labels him, fails in his mission. Instead, the rocket ends up marooned on the Moon where it will act as the foundation for the forthcoming Moon base.

As Gen. Greene, Hayden gets the thankless task of reciting all of the pseudoscientific exposition. And in one incredibly "yeeugghh" moment, Gen. Greene calls Col. Briteis a "spoiled brat" and says that if she doesn't stop giving him "guff" about Maj. Moore piloting the rocket, he'll take the colonel over his knee and spank her. She says that she'll scream, he remarks that his office is soundproof—yeeugghh! He also gets to have a man to man talk with Maj. Moore about his feelings for his superior officer, Col. Briteis—who, BTW, everyone continually calls "Bright Eyes" even though she keeps reminding everyone that that is not her name. The general and major have to sort all this out because there's a big problem if Ford and Briteis are to man the Moon base solo until construction can begin: the American public of futuristic 1970 will absolutely not tolerate a woman and a man living together in sin. Not only that, Briteis insists that Ford be promoted to a rank above hers so that he can command the makeshift base. So, in case you were wondering, Project Moonbase ends with a wedding. Fun fact: Robert A. Heinlein's original script was titled "Ring Around the Moon." [Rimshot]

To call Project Moonbase a film is too generous—and everyone involved with the production would most likely agree. Project Moonbase was originally the pilot for The World Beyond a proposed sci-fi anthology series from movie producer Jack Seaman. For the test episode's script, Seaman hired highly popular and influential author Robert A. Heinlein. Hollywood was already interested in Heinlein's work; 1950's groundbreaking sci-fi film Destination Moon lifted off from Heinlein's short story Rocket Ship Galileo, and three more of the author's shorts were adapted into episodes of the very short-lived CBS anthology Out There. Hayden was not going to turn down the chance to act in something written by such a popular author, not while he was still getting a hold in television.

Filming on The World Beyond lasted just 10 days, which feels right for an hourlong TV pilot and disastrously wrong for a feature film. The production, directed by stuntman Richard Talmadge, was unforgiving. This is best evidenced by the press conference scene wherein Gen. Greene talks for nearly three and a half minutes, including one minute-long monologue of scientific gibberish.

The scene: gossip columnist Polly Prattles (played by Hayden's friend Barbara Morrison) asks the general to tell her something about this "wonderful" space station. Hayden, as Greene, then tries his damnedest to tell her a whole minute of somethings:

Greene: Well, I can give you a rough idea. The station is a titanium hull [beat] with steel bracing [beat] 350 [beat] feet in diameter. It rotates completely around the Earth in a trans [beat] polar orbit about 10 times a day. [4 seconds of silence] At present, the station is in the state of freefall

Prattles: Freefall? Could you explain that a little more?

Greene: Of course. When we speak of freefall, we simply mean that [beat] the station and everything in it are moving around the Earth [beat] at a speed which is [beat] great enough so that [beat] it can't fall toward the earth. But it is also [beat—Hayden starts to smile slightly] moving at the speed which is not great enough [beat] in order to enable it to go out into space. Therefore, the forces of gravity and speed are now in balance. And as a result, nothing in the station has any weight.

That moment when Hayden starts to smile slightly, as if he's acknowledging the absolute ridiculousness of this situation, is likely one of the very few on-camera instances of Hayden Rorke struggling to not break. He's also truly struggling and no one helped him. Talmadge didn't call "cut." They didn't let him take the monologue piece by piece and cover it up with cutaways, even though this is a press conference with ample opportunity for reaction shots. They didn't even let him try again! Hayden said all the words, probably, and that was good enough. Now put on your swimming cap and short shorts and get ready for the next scene!

The pilot wrapped and Seaman started shopping The World Beyond around at what turned out to be a rough time for sci-fi on TV. The swift termination of Out There in early 1952 and the end of another sci-fi anthology, ABC's Tales of Tomorrow, in spring 1953 may have led every network to pass on the pilot for The World Beyond. The sci-fi anthology was probably done as far as ABC and CBS were concerned. The genre wouldn't come into pop culture power until The Twilight Zone's debut six years later.

Another possible strike against the finished pilot may have been that it was actually—believe it or not—too feminist. In his book The Spacesuit Film: A History, 1918-1969, author Gary Westfahl points out that Project Moonbase does star Donna Martell playing the commanding officer, even if it's revealed up top that she's only a colonel because she weighs less than the men and was therefore more suited to early space travel. Also Moonbase included Ernestine Barrier as Madame President. Westfahl cites NBC's rejection of Star Trek's initial pilot episode "The Cage," in part because execs thought audiences would bristle at Majel Barrett playing the high-ranking role of Number One. That was in 1965. Project Moonbase was shopped around over a decade earlier. Project Moonbase was just ahead of its time.

Instead of sitting on 50-something minutes of finished footage with Robert A. Heinlein's name attached, producer and co-writer Jack Seaman padded Moonbase out to 63 minutes and shopped it around as a feature film. Lippert Pictures, known for its quantity over quality ethos, snatched Project Moonbase up and rather unceremoniously dropped it in theaters on September 4, 1953. Reviews were unsurprisingly unkind, with Variety belittling Martell as a "cute little trick" and saying that Ford "delivers amateurishly." Regarding Hayden, Variety wrote that the general "talks without saying anything." Okay, Variety, you try explaining the concept of freefall in one take.

While these reviews are clearly not wrong, they don't feel entirely fair. Project Moonbase was never intended to be placed in the crosshairs of movie critics. It was supposed to be a disposable hour of televised entertainment, which is why it was shot on a TV schedule with a TV budget and re-used sets from Cat-Women of the Moon—a movie that opened on the same weekend to wildly better reviews. Cat-Women of the Moon—!

For some reason, though, Project Moonbase found a second life when it became one of the first films to enter constant rotation on television at the top of 1956. If you were bored on a weekend afternoon or stayed up past your bedtime anytime from 1956 to the turn of the last century, odds are you'd flip past Project Moonbase and possibly even stop for a second to catch Dr. Bellows threaten to spank a grown woman.

Ever the good sport, Hayden would spend the rest of his life getting a kick out of having appeared in Project Moonbase. He would even bring it up in casual conversation, boasting that he once appeared in "the worst movie of 1953." He'd laugh about those "little hats" and the cheap special effects for the rest of his life. Hayden was never embarrassed by Project Moonbase playing at midnight every night on some channel across America. After all, Project Moonbase was meant to be watched on television.

Films, Selected

-

Lust for Gold (1949)

-

Rope of Sand (1949)

-

Kim (1951)

-

Father's Little Dividend (1951)

-

Double Crossbones (1951)

-

Francis Goes to the Races (1951)

-

An American in Paris (1951)

-

When Worlds Collide (1951)

-

Confidentially Connie (1953)

-

South Sea Woman (1953)

-

Project Moon Base (1953)

-

Lucky Me (1954)

-

A Stranger in My Arms (1959)

-

Pillow Talk (1959)

-

Midnight Lace (1960)

-

The Night Walker (1964)

-

The Barefoot Executive (1971)